Many authors, literary critics, and High School English teachers conflate a book’s “theme” and “controlling idea” into the same concept, implying both terms mean the message of the book.

I prefer to differentiate the two concepts.

I see theme as something that can emerge (often unconsciously) in the drafting of a manuscript, whereas a controlling idea is something an author will benefit greatly from having considered during the planning stages prior to drafting.

Let’s start this discussion with theme and then move on to controlling idea.

Theme

A theme is a recurring story elements or motif within a narrative. These elements can be settings, actions, ideas, narrative phrases, and lines of dialogue.

Sparknotes defines theme as “the fundamental and often universal ideas explored in a literary work,” and motifs as “recurring structures, contrasts, and literary devices that can help to develop and inform the text’s major themes.”

Themes and motifs provide narrative unity, pattern formations, and overall coherence to a book or narrative.

I find it helpful to think of rock music when considering theme.

Most rock songs consist of only a handful of structural elements: the intro riff, the verse (which is often a variation on the intro riff), the chorus, the bridge, and, perhaps, a guitar solo. The organized repetition of these elements, with each element becoming recognizable and familiar to the listener upon its return in a song, is part of what makes rock music so enjoyable.

Some of the most common thematic elements appearing in English literature (returning again and again throughout a novel the way a song eventually returns to its chorus) are: love, death, betrayal, nostalgia, loneliness, good versus evil, freedom, love, friendship, war, fear, perseverance, revenge, death, sacrifice, and divinity.

Themes appear in a manuscript via two methods: repetition of wording and thematic patterning.

Repetition of Wording

Sometimes referred to as “Leitwortstil” (which translates to “motto style” or “leading-word style”), repetition of wording is one way themes can emerge in writing, sometimes unconsciously, on the part of the author. Originating in the field of biblical textual studies, Leitwortstil refers to the repetition of specific phrases or words throughout a text, which gradually draws the reader’s attention to a theme.

The word “blood” appears throughout Shakespeare’s play Macbeth, continually drawing attention back to the theme of murder and the guilt felt by the play’s protagonists King and Queen Macbeth.

Similarly, the line of dialogue, “I have a bad feeling about this,” appears in all eight Star Wars films, creating a thematic thread throughout the movie series.

One of my favourite uses of repetitive wording is the call back.

A call back happens when a phrase used early on in a story is repeated again near the story’s end. Due to the events that have transpired in the story and the changes those events have had on the world and the story’s characters, the phrase takes on a new level of meaning and depth it didn’t contain when it was first used.

The line, “I’ve never been the emotional type,” appears on the first page of my novel, M School. The phrase appears again on the final pages of the book. If I’ve done my job well as an author, the phrase produces a very different impact on the reader the second time it appears in the novel. Stephen King’s book Needful Things similarly returns to where it began, describing the opening of a new store, similar to the one the book was about, only now in a different town. The “rules” of Fight Club are repeated throughout the text, a technique author Chuck Palahnuik specifically refers to as the use of “choruses”. (See rock music metaphor in this article’s opening.)

K. Chazda Albright suggests Leitwortstil is particularly effective in kid’s books and outlines three reasons why in this article.

Repetition of wording can also be used to great comedic effect in the form of running gags, catch phrases, and including call backs to earlier jokes as part of a later jokes. Marc Maron’s stand-up performance, “More Later,” repeatedly returns to that title phrase throughout the set, producing both thematic unity and comedic impact.

Thematic Patterning

A less obvious, but still powerful, way of inserting theme into your manuscript is the use (or emergence) of thematic patterning. Thematic patterning is not the reoccurrence of specific language, as with Leitwortstil, but rather the reoccurrence of ideas, concepts, images, and moments, often in the form of motifs.

If we return to our example of Star Wars, there is much thematic patterning to be found in the series in the form of space battles, laser sword fights, the loss of limbs, and the mechanization of the human body.

Often thematic patterning is the result of generic conventions, genre tropes, and obligatory scenes. And, as such, certain themes often recur in certain types of books and stories; think, for example, of the common themes of brotherhood, honour, and sacrifice so often found in war stories.

Thematic patterning can also occur throughout the oeuvre of a particular author. Stephen King’s books often feature regular everyday American’s forced to face fantastic and deadly threats. The writings of war veteran’s Kurt Vonnegut (WWII) and Earnest Hemingway (Spanish Civil War) often return to the topic of war.

In my own case, it was only after I had written three novels that I noticed common motifs throughout, including bullying, violence, and teenagers’ difficult relationships with their parents and step-parents. I didn’t set out to continually write about those topics, yet when I looked back on my work the themes consistently appear in some shape or form – a clear example of thematic patterning emerging subconsciously.

Controlling Idea

Whereas thematic patterning can emerge subconsciously, a book’s controlling idea should be clearly understood by the author at the beginning of the drafting process. The controlling idea is, after all, why you are writing the book. It is the beating heart of your novel, the message of your story. It’s what you, as an author, have to say about the world, or want to teach the reader. It’s your book’s big takeaway.

Author Ryan Holliday recently drew attention to a great quote from Brand Blanshard’s book, Four Reasonable Men, regarding why we still read the work of Marcus Aurelius:

“Few care now about the marches and counter marches of the Roman commanders. What the centuries have clung to is a notebook of thoughts by a man whose real life was largely unknown who put down in the midnight dimness of not the events of the day or the plans of the morrow, but something of far more permanent interest, the ideals and aspirations that a rare spirit lived by.”

What authors can take away from this quote is that readers won’t be moved by the “marches and counter marches” or plot machinations of your novel; rather, it will be “the ideals and aspirations” that will leave their mark on the reader, i.e. your book’s controlling idea is what will have impact.

As I’ve written about before, many people become authors later in life. I suspect this may have something to do with the wisdom and experience of age allowing for the formation of clear controlling ideas. In youth, few of us have a confidence bred from experience and often hardship to allow for the articulation of a clear world view. In his book Do the Work, Steven Pressfield confesses:

“I was thirty years old before I had an actual thought. Everything up till then was either what Buddhists call ‘monkey-mind’ chatter or the reflexive regurgitation of whatever my parents or teachers said, or whatever I saw on the news or read in a book, or heard somebody rap about, hanging around the street corner.”

Robert McKee discusses the controlling idea in his book Story, arguing that a controlling idea must be boiled down to the fewest possible words and delivered in a single sentence.

The controlling idea I worked with for M School was sociopathic behavior leads to unresolvable cycles of violence. Though never explicitly stated in those words, that simple sentence is what I want readers to take away from the book. It, therefore, informed many of the decisions I made during the drafting process.

As Sean Coyne puts it when discussing the controlling idea, “The writer never explicitly states them. Instead the reader intuits the message from the actions and results of those actions in the Story.”

—

So… what is YOUR book about?

What’s your controlling idea?

Thematic patterning is inevitably going to emerge as your write. The preoccupations of your subconscious will ensure they work their way into your manuscript, but what you have to say about the world needs to be clear to you; otherwise, it will never be clear to the reader.

Conflating theme and controlling idea into the same concept may have been alright for your grade 12 English essay, but as an author you’ll want to separate the two concepts. Let theme emerge in the writing, but lock down that controlling idea before you begin to draft.

—

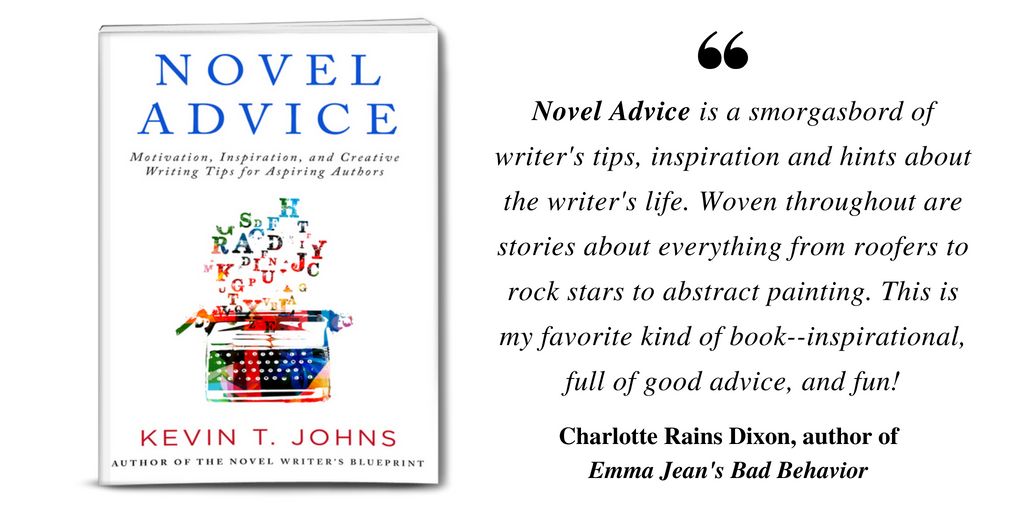

Enjoy this article? If so, you’ll love Novel Advice: Motivation, Inspiration, and Creative Writing Tips for Aspiring Authors. Grab a FREE copy by clicking the image below: