In episode 158 of The Writing Coach podcast, I explore the powerful role that change plays in storytelling. Change impacts the characters and the world of your story but also the reader themselves. You’ll learn about the transformative nature of storytelling and the undeniably powerful writer’s craft tool that change can be for an author.

Listen to the episode or read the transcript below:

The Writing Coach Episode #158 Show Notes

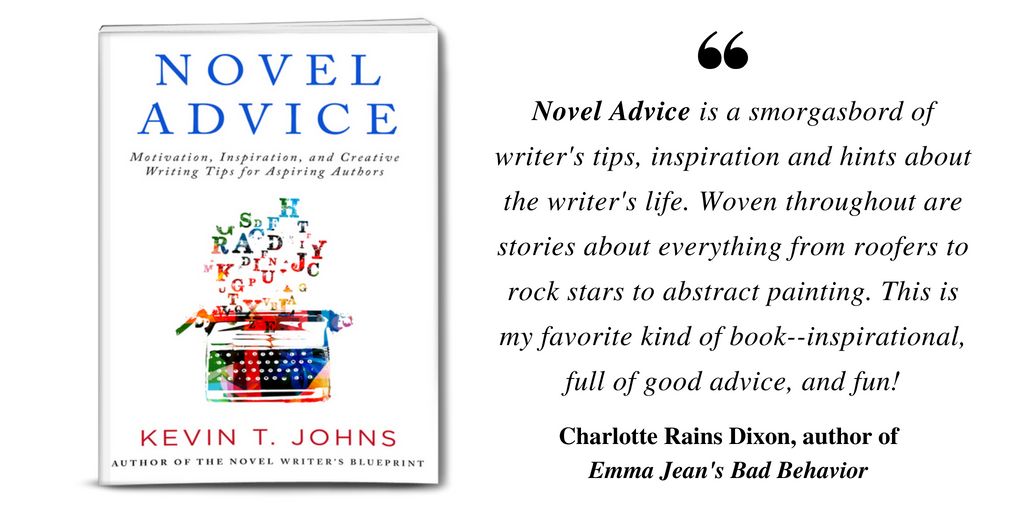

Get Kevin’s FREE book: NOVEL ADVICE: MOTIVATION, INSPIRATION, AND CREATIVE WRITING TIPS FOR ASPIRING AUTHORS.

The Writing Coach Episode #158 Transcript

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Hello, beloved listeners, and welcome back to The Writing Coach podcast. It is your host, as always, writing coach Kevin T. Johns here. And today it is time to face the Strange. Yes, we are talking about Cha cha cha changes in story.

But first, do you want to get a free book? If you’d like a copy of my book, Novel Advice: Motivation, Inspiration, and Creative Writing Tips for Aspiring Authors, head on over to www.kevintjohns.com. There’s a tab at the top that says, free book. That’s where you can drop your email in and get a copy of novel advice.

Now, today we’re talking about Cha cha cha cha changes, as I said, but first let me tell you a story, okay? The other day it was super hot here in Ottawa, and I really wanted an ice cream. So I started walking towards the corner store, and on the way to the corner store, I actually ran into my friend Gary.

I said, “Gary, what are you up to?” And he was off to pick his kids up from swimming class. And so that was great. He continued on to go pick up his kids, and I went to the store to get my ice cream. It was pretty awesome.

All right, <laugh>, what’s going on here, folks? That was not a very good story, was it? Now, why was it not a good story? Well, largely because nothing changed other than, yeah, I guess I got my ice cream at the end of it, but I didn’t run into trouble getting the ice cream. There were no complications or drama along the way. And so if you find yourself looking at your story or reading a book, and you have this feeling where you’re like, nah, it’s just not that good, for some reason, ask yourself, is anything changing?

Because once you ensure that there’s change taking place in the story, then drama starts happening. Lisa Cron is a great writing instructor. She has a book called Story Genius. And I’m going to paraphrase here, but I believe her definition of a story is that story is about someone who wants something, who takes action to get it, encounters obstacles, and is changed as a result. So right there in Lisa Cron’s definition is that key component of change. And so when we’re looking at stories, and we were asking ourselves, is there a change in the story? Where this is generally most obvious is at the character level. Most people are familiar with the concept of a character arc, which means your character is a different person at the end of the story than they were at the beginning. Now, this could be for the better or for the worst.

Often we see positive change arcs. These are coming-of-age stories, or these are stories where the good guy ultimately wins in the end. And we have a character who starts in a place of lack or who starts with a wound or a misunderstanding about the world and who goes out on their adventure or who encounters obstacles on the way to try to achieve something. And as a result, they’re changed for the better. They realize that the thing that they were lacking, they’re able to attain. Perhaps that’s love, or perhaps that’s a professional accomplishment, or perhaps that’s, you know, a sword, right? <Laugh>, they were missing something and by the end of the story, they have it, or they’d have a better understanding of how the world works. They were perhaps naive, and they finished the story more wise, or they were cynical at the beginning of the story, and they end the story much more accepting of, of positivity, right?

We start in one place, we end in another. And if we’re ending in that positive place, then we have to reverse engineer that story and ensure that our characters are starting from a negative place, starting from a place of lack. That’s what we call a positive change arc for our characters. But of course, life isn’t all sunshine and roses and characters don’t always change for the better. In fact, sometimes it’s our character’s resistance to change that ultimately leads to their downfall. And so stories then end with our protagonists in a negative space are called negative change arcs. This is the opposite of our positive change arcs. And we see this all over the place in the tragedies as a father with a bunch of daughters <laugh>, I particularly relate to King Lear, who starts his story out as a powerful wise king and ends up as a madman screwed over by his children.

<Laugh> That one, there’s a negative change arc that resonates with a father. But of course, there are lots of great tragedies and lots of great sad stories that start with a character in a place of power and confidence and ultimately end in ruin and often death. If in the case of let’s say Macbeth or Hamlet or even Romeo and Juliet. These are characters who start with Hamlet wanting revenge, with Mc McBeth, wanting to be king, with Romeo and Juliet perhaps wanting to find true love, and all of them ending in ruin and disaster. And there’s our change. That’s why Shakespeare knew what he was doing: how these stories end is the opposite of how they begin. And we can return to our positive change arc when we’re talking about Shakespeare’s comedies, right? When we look at A Midsummer Night’s Dream, we have all these couples who are all separated, and by the end of the play, they’re all together in their proper relationships and married, they go from this place of lack to a place of wholeness and change has taken place.

And when that happens, we feel like we got a good story, whether when in the audience in the Rose Theater 400 years ago, or whether we’re sitting in our living rooms reading an eBook on our telephone. Either way, it’s that sense of change in the character that really makes us feel like something happened in the story. But of course, here’s the thing, not every character changes, particularly when we’re looking at archetypical characters like say Superman, or when we’re looking at characters in a series, we can talk about someone like James Bond. I would argue that the reason the James Bond franchise was successful for 50 years was that James Bond did not change very much over the course of his films or from film to film. And I would argue that the Daniel Craig Bond films are some of the worst Bond films in the history of James Bond. And that is p possibly because they tried to give Bond a change Ark, I’m not going to go down the bond rabbit hole, but I will say Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, understood that with a character, an archetypical character like James Bond, or perhaps a superhero character, or a character who represents stability and authority in society, we can think about detectives, we can think about police officer characters, we can think about firefighters, think about stories about doctors.

In all of these stories, often our protagonist does not change. There is not a change arc, but there is still change in the story because the world is generally changed by antagonistic forces. So the world’s going along well, all is good, but then Blofeld inspector wants to blow up the moon or take over the earth or do whatever, and the world is thrown into a state of chaos, and it becomes our figure of the status quo. It becomes James Bond’s mission to get out there, defeat the bad guy, and return the world to a state of status quo to take us out of chaos. We can think about the Western as well. We can think of the outsider who comes into the small town that’s overrun by bandits, and he defeats the bandits, saves the town, and then rides off into the sunset. Well, why does he ride off into the sunset?

Because he can’t be domesticated. If he came into the story an outsider and then remained in the town an insider, that would be an arc. But in these sorts of stories, we are heroes right off into the sunset because they can’t stay in the town. They have to continue on to the next adventure. And so that’s why in stories like comic books and in James Bond. Let’s use our medical or our firefighter example in the story about a firefighter. The world is at peace, and then a fire breaks out. What’s changed is the chaos of the fire. Our firefighter protagonist encounters obstacles. Maybe there’s a backdraft, maybe the fire’s on the 40th floor of an apartment building. They have to do all these things to put that fire out, but ultimately they’re able to do so, and the world is returned to a state of calm and peace.

And so the same with doctors. Everything’s going all right, and then someone gets shot, our hero doctor goes in there, saves the day in returns to the patient to a sense of status quo. So there are two options right there for, well, I guess we’ve discussed three options already, right? Positive change arcs, negative change arcs, and then stories in which the world is changed and needs to be returned to a state of status quo. Now, in her book, Save the Cat Writes a Novel, Jessica Brody makes a really interesting observation about the Whodunnit genre, which in Save the Cat terms is called Whydunnit? I think because they’re trying to get who, what, where, where, why into the mystery genre. The point being, I found this particularly fascinating, particularly because I’m interested in dark stories.

I’m interested in violent bad guys and gothic storytelling, and in Save the Cat Brody says that when we read a Whydunnit, when we read these dark mystery thrillers, often it’s the reader who is changed. Oh, we’re, we’re getting Medicare folks. So not only is perhaps the world thrown into a state of chaos and needed in need of being returned to the status quo, we as readers are changed by witnessing the levels of darkness that humanity can potentially stoop to. And also probably the levels of heroicness that mankind’s inhumanity can rise to in response to darkness. I think about this, particularly in the context of Thomas Harris’s amazing novels, Red Dragon, and Silence of the Lambs and less so the book, Hannibal. But certainly the TV show, Hannibal, which is based on those books, Harris’s books, and I think Hannibal is one of the greatest television series ever made, and it’s also one of the most disgusting and horrific and bleakest television shows ever made.

And so I asked myself, you know, why, why do I love watching these stories so much? Why do I love reading about Hannibal Lecter? And I, I think part of it is what Brody’s talking about is that we, we get a better understanding of, of, of what humanity is capable of when we hear these stories of, of utter darkness. And in doing so, I think it might perhaps make us appreciate the goodness that we have in our lives and, and the goodness in the people around us and maybe some of the things that we think are so horrific aren’t nearly as bad as, as what my mankind is truly capable of. And so we’re changed, we’re changed in the reading of the story. Now, these sorts of dark stories that reveal horrible aspects of humanity, they’re not the only types of books that change readers.

The non-fiction genre is almost primarily focused on changing the reader. Particularly how two stories, particularly self-improvement books, if you pick up and read a book about diet and exercise, you as a reader are going into that book hoping to be changed. You’re hoping that the information in that book is going to allow you to institute protocols that allow you to change your life and change your body and change your health.

Same with reading a book about writer’s craft. When you go to my website, www.kevintjohns.com, and you download Novel Advice: Motivation, Inspiration, and Creative Writing Tips for Aspiring Authors, it’s because you are hoping that the information inside that book is going to change the way you write or change the way you think about writing or change the way you come at your art. And as a non-fiction author of that book, that’s my goal. I’m trying to write non-fiction that transforms the reader. And so in these non-fiction books, it’s the reader again, who is being changed.

So we’ve covered a bunch of different types of change here, but what we’ve been talking about is all at the macro level, right? We’ve been talking about characters who change over the course of a book, or we’re talking about readers being changed by reading a book. But as per my Estonia doll method, what I believe in writer’s craft works at the macro level almost always works at the micro level as well. And it’s often at the micro level, the scene-by-scene level that writers aren’t giving as much analysis to things like change in their story. But I would argue that at the scene level, something needs to change every single scene. This is something that Shawn Coyne talks about in The Story Grid, which he calls turning points. He makes the argument that every scene needs a turning point, a point of change that either transitions on external action, something happens externally to our character, that changes the trajectory of the scene or the revelation of information, new information comes to light that again, changes the direction of the scene.

So maybe the scene things were going good and then they go poorly because of something that happened externally, or maybe things were going bad, but then there’s a revelation of information that makes things go good by the end of the scene. The point is we are looking for change in our stories, and I would say where the writers that I work with are failing to think about change is really at that scene level. So everything that we’ve talked about here, when we’re talking about characters changing, when we’re talking about environments changing, you want to be taking these same concepts and applying them to every single scene in your book and really ensuring that things change far too often. I’ve read scenes where stuff happens, but nothing changes. And it brings us full circle back to my story about going to the store and buying some ice cream and running into a friend along the way.

That’s just not like no ice cream to having ice cream with no complications along the way is just not interesting or dramatic enough to feel like something worthwhile actually happened in that story to make it worth the telling.

So you want to tell good stories? You want to entertain people? You want to write incredible books? Start with change. Think about how the world of your book is going to be changed by the events of it. Think of how the characters are going to be changed for the better or for the worse, or, or, and or <laugh>. Think about how you’re going to change the reader in how they see the world or how they go about living their life.

All right, that is it for this episode. To grab Novel Advice: Motivation, Inspiration, and Creative Writing Tips for Aspiring Authors, head on over to www.kevintjohns.com. That’s also where you can find the show notes for this episode. I do a transcript of every episode, so if you want to read what we just went over, you can check it out there. And of course, I would love it if you hit that subscribe button so that I can see you on the next episode of The Writing Coach.