In this episode of The Writing Coach podcast, writing coach Kevin T. Johns continues his review of the Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist tool and discusses the importance of:

- Scene Goals

- Proper Tense

- Scene Structure

- Decision Points

- Polarity Shifts

- Progressive Complications

- Openings and Closings

- Pacing

Listen to the episode or read the transcript below:

The Writing Coach Episode #172 Show Notes

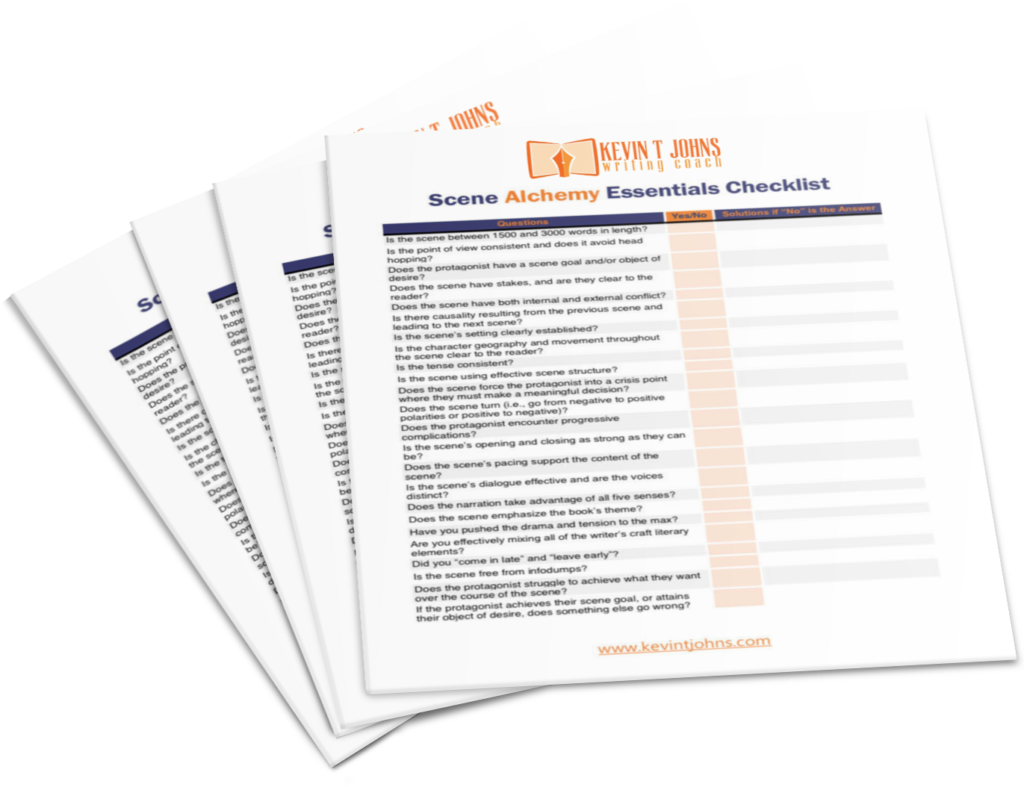

Download the FREE Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist Now!

The Writing Coach Episode #172 Transcript

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Hello, beloved listeners and welcome back to The Writing Coach podcast. It is your host, as always, writing coach Kevin T. Johns here.

Last episode, I introduced a super cool new tool called “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist.”

This checklist is a list of over 20 questions you can ask yourself when analyzing a scene, and if you can’t answer “yes” to all of these questions, then there’s probably an opportunity for you to improve your scene.

If you’ve ever sat down and looked at your work and looked at the scene and said, “I have no idea how do we improve this?” That is what this tool is all about. Get your copy here.

Last week on the show, we covered the first five or six questions of the checklist. This week, we are going to continue that discussion. But I have to say something: last week, I missed one of the questions, and it is one of the most important questions a writer can ask themselves about their scene. And that question is:

Does the protagonist have a scene goal or an object of desire?

In Western storytelling, most of the time, we are looking for agency-driven characters. We want characters to be driving the story. We don’t want things happening to our characters. We want them to happen because our character has taken action, and what’s driving that action, what’s motivating them, is the scene goal.

That scene goal could be anything, but sometimes it’s a specific object of desire. Let’s think about Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, the big opening sequence. What’s Indie’s sequence goal? Get in there, get that golden idol and get out in one piece. Much more often, though, the scene goal can be to convince someone of something, or to find evidence, or to have a good date.

The point is that every time you write a scene, your point of view character’s actions need to be clearly driven by some internal desire and not just reacting to things that are happening to them. When that happens, I call it “pinball syndrome.” It feels like your character is in a pinball machine, and they’re just being knocked around by the paddles of fate. It really saps the story of energy, and it makes everything feel coincidental or overly determined and fated. We really want our characters to have desires and to take action to try to achieve them. And, of course, run into trouble trying to get to them. That is the question I missed last week. Make sure you’re asking yourself, “Does the protagonist have a scene goal?”

Is the scene’s tense consistent?

Are you writing in present tense? Or are you writing in past tense? And are you remaining consistent throughout your narrative?

Both past and present tense have different benefits and drawbacks. I would argue there’s an immediacy to present tense; there’s a very modern feel to writing in the present tense. I think it’s great for things like Young Adult or maybe action novels where things are happening in the moment and we’re reacting with the energy or emotions of a teenager or a person in that action situation or whatnot.

Whereas I find third person so much better for a sense of legend, a sense of this is something that happened in the past that is now being related via a storyteller. For example, I couldn’t imagine Lord of the Rings written in present tense. It’s this feeling of an ancient time.

Both present and past can work. You want to choose the one that makes the most sense for the story that you’re telling. And then you want to make sure you’re being consistent throughout the narrative.

Are you using effective scene structure?

We hear so much about macro-level story structure, the hero’s journey, the three-act structure, four structure, the Elizabethan five acts structure. Everyone’s heard about this stuff, but we don’t hear nearly as much about scene structure There’s a few different ones that I like to recommend.

There’s James Scott Bell’s LOCK method where you look at your scene’s lead, their objective, the conflict that they encounter, and some sort of knockout ending to the keep the reader reading.

There’s also Cathy Yardley’s GMCD method where you identify your character’s goal, you identify what their motivation is, you add in conflict, and then there’s a disaster, something goes wrong at the end of the scene so that we keep that tension up.

There is Shawn Coyne’s Five Commandments of Storytelling, which are inciting incident, progressive complications, crises, climax and resolution.

I tend to use a structure where the character takes an action towards a goal, encounters progressive complications that push them to a decision point, they act on that decision point, and then we get a thrust-and-twist cliffhanger ending.

You’ll notice that all of these different structures largely are trying to get at the same thing. We have a character who’s motivated to achieve a goal. They run into complications in the process and are forced to react. That is scene structure. Make sure you familiarize yourself with it, but also that you execute on it in your scenes.

Does the scene force the protagonist into a crisis point where they must make a meaningful decision?

I just mentioned decision points in the story structure that I like to use. Decision points are fascinating. The second you force your character to make an important decision, the scene comes alive with energy. There’s so much built in conflict and tension to having a decision that has opposing sides.

In The Story Grid, Shawn Coyne lays out the “best bad choice” decision point. The best bad choice is when neither option is good. Your character is faced with two bad options, and they’re forced to pick one. The other is “irreconcilable good,” which means one good choice precludes the other good choice. You have two children, and you get to choose which one lives, but the other one dies. That is an irreconcilable goods decision point.

What you’ll find is the second you put those decision points into your story it ups the drama, it ups the tension, it also gives our character that agency we’ve been talking about because they’re taking action, they’re making a decision, and then they’re acting on it. Of course, not making a decision or choosing not to act can be a decision itself.

But looking at one of your scenes, ask yourself, “Is my character being forced to make an important decision here? And if not, can I add decision?” It will almost always improve your scene.

Does the scene turn?

This is something Shawn Coyne talks about a lot in The Story Grid, this idea of scenes going from negative polarities to positive polarities, positive to negative, negative to double negative, positive to double positive. The point is that the valiance of the scene shifts somewhere along the way. It starts in one polarity: happy, and it ends in another: sad.

Why are these turns important? They’re important because story is about change, and if there isn’t a change in polarity within any given scene, it’s likely that scene is pure exposition.

We’ve all been there: we read 20 pages, and then we close the book and we go, “You know, I just read 20 pages, and I don’t feel like anything happened.” How do you read 20 pages of a book in which nothing happens? Well, it’s because nothing has changed. When things change, the reader goes, “Oh, okay, that moment in the story was important because things are different now.” So when we’re asking ourselves, if the scene turns, if the scene shifts in polarity, what we’re really asking ourselves is, does this scene matter? Does the scene actually change the trajectory of the story? Because if it doesn’t, that scene can probably be cut.

Does the protagonist encounter progressive complications?

This goes back to our scene structure question where we’re asking ourselves, does our character ever goal are they taking action to get it, and then are they encountering barriers, challenges, and obstacles in the way.

My favorite examples of progressive complications takes place in Moana. Moana tries to get past a barrier reef that serves as a bit of a wall around her community, her Island. She gets on a boat, and she attempts to get across this barrier. That’s her scene goal: get across the barrier. What’s the complication? A giant wave hits her knocks her off of her boat. Great, that’s drama. That’s great conflict. But what the writers of Moana do is they add progressive complications. Next, she’s swimming in the water and a wave hits her in the face. Now she’s underwater, and she’s dragged down to the bottom of the ocean by the current. We have our first complication, a wave knocks her off the boat, we have our next complication, a wave knocks her deep underwater. We see the second complication is more complicated or has greater stakes than the first one. That’s why we’re talking about progressive complications, not just a bunch of complications, but complications that get worse than the one that preceded it.

Once Moana finds herself at the bottom of the ocean, her foot gets stuck under a rock, and she’s going to drown. So again, by adding progressive complications, the writers of that scene have created excellent drama. They keep ratcheting it up by throwing more and more problems at Moana.

Ultimately, it forces her into a meaningful decision point: am I going stay underwater and drown or am I going to yank my foot out from under this rock and probably severely hurt my ankle in the process? Of course, what happens is she yanks her foot out, and she washes up on shore with a bloody leg.

There’s a great little scene about a character who’s motivated to achieve a goal and then who encounters progressive complications that force her into a meaningful decision. That’s storytelling, that’s drama and conflict. That’s what good scene writing is all about. When you’re sitting down, and you’re analyzing your work, ask yourself, “Are there enough complications in here? And are the complications progressing? Are they getting more and more intense?”

Are the scene’s opening and closing as strong as they can be?

Next up is a really easy one because you can do it via sweeps. In the revisions process, sometimes people think you need to revise the way you write, in terms of sitting down and writing scene one and sitting down and writing scene two. And then when it’s revisions time, you sit down and you revise scene one, and then you revise scene two. But it doesn’t have to be like that. You can go through the whole book, looking for just a couple of elements. I think this question is a really great one that you can do that sweeps process, with in that’s “Are the scenes opening and closing as strong as they can be?”

Take a week and go through your manuscript and say, is the opening to every single scene gripping? Does it hook the reader? Does it make them want to keep reading? And do we have great endings to those scenes that make the reader want to keep reading? What are you doing to ensure that when the reader reaches the end of that scene they don’t close the book and go to bed? What sort of open loop? What sort of question? What sort of cliffhanger? What sort of shocking revelation can you have at the end of your scenes to make the reader keep reading late into the night?

A really simple piece of advice to keep in mind when it comes to beginnings and endings to scenes is to come in late and leave early. Quite often, we have recap paragraphs at the beginning of chapters where the author is bringing the reader up to speed on what happened in between scenes. Or perhaps we have a character parking their car and walking up to a house and going inside and then having a conversation. Where the drama in the scene located is when they’re inside talking so start there. Come into the scene late.

Don’t start the scene when the character wakes up in the morning; start when they arrive at work and the interesting thing happens.

The same thing with endings. Sometimes we stick around in a scene a little too long, and we’re getting a little boring, perhaps, or just spending a little too much time in that moment. Look at your scenes and ask yourself, if I cut off the last paragraph, if I cut off the last three paragraphs of this scene, will it actually be a more dramatic ending? Will it accomplish that goal that we want of having the reader turn pages and keep reading?

Does the scene’s pacing support the content of the scene?

Pacing is the speed at which the reader moves through the story. We can control this with showing and telling. You’ve probably heard the advice: show, don’t tell. That’s not actually good advice. The better advice is: show the dramatic stuff, tell the boring stuff.

We don’t need to hear James Bond getting up, brushing his teeth, going to the bathroom, eating cereal and putting on a tie. We need to see James Bond in battle with the bad guy. And so when they’re in battle, slow the scene down by using lots of language, by giving us all the details of the moment. But when it comes to breakfast, speed on through: “James Bond woke up, ate breakfast and headed out the door.” That’s all we need. We don’t need to know that he ate Cheerios that morning because it’s not interesting and it’s not dramatic.

When you’re looking at a scene, try to find the most dramatic parts, the most interesting parts, those decision points that we’ve been talking about, those polarity shifts, those moments of revelation because those are the golden nuggets.

We’re talking about scene alchemy, here; we’re talking about turning words into gold.

With any given scene you’re looking at it in the revisions process, you’re like a gold prospector. The scene is a pile of dirt—no offence to your writing. But when you take that pile of dirt, and you sift it, what you’re doing is you’re looking for those dramatic, exciting, cool, interesting, shocking moments. Those are the little pieces of gold that you’re looking for. And once you found them, once you’ve drafted the scene, and you said, “Oh, this part was much more exciting than I thought,” that’s where you want to dedicate your word count. That’s where you want to show. That’s where you want to get into details. And some of the other parts of the scene that perhaps aren’t as interesting, aren’t as dramatic, well, maybe you pull back on the word count there so that we move through the boring stuff quickly and get to the good stuff.

All right, that is it for our second look at “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist.” We’ve still got several questions to go, so we will tackle those on our next episode. I really want you to grab the scene checklist. I think you’re going to find it super helpful in analyzing and improving your scene-by-scene writing. Get it here.

Thank you so much for tuning in. Remember to hit that subscribe button so that you can hear the next episode, where we will continue to walk through the various questions included in “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist.”

I will see you there, on the next episode of The Writing Coach.