In this episode of The Writing Coach podcast, writing coach Kevin T. Johns continues his review of the Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist tool and discusses the importance of:

- Dialogue

- Sense Descriptions

- Theme

- Pushing drama, emotion, and tension to the max

- Coming into scenes late and leaving them early

Listen to the episode or read the transcript below:

The Writing Coach Episode #173 Show Notes

Download the FREE Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist Now!

The Writing Coach Episode #173 Transcript

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Hello, beloved listeners and welcome back to The Writing Coach podcast. It is your host, as always, writing coach Kevin T. Johns here.

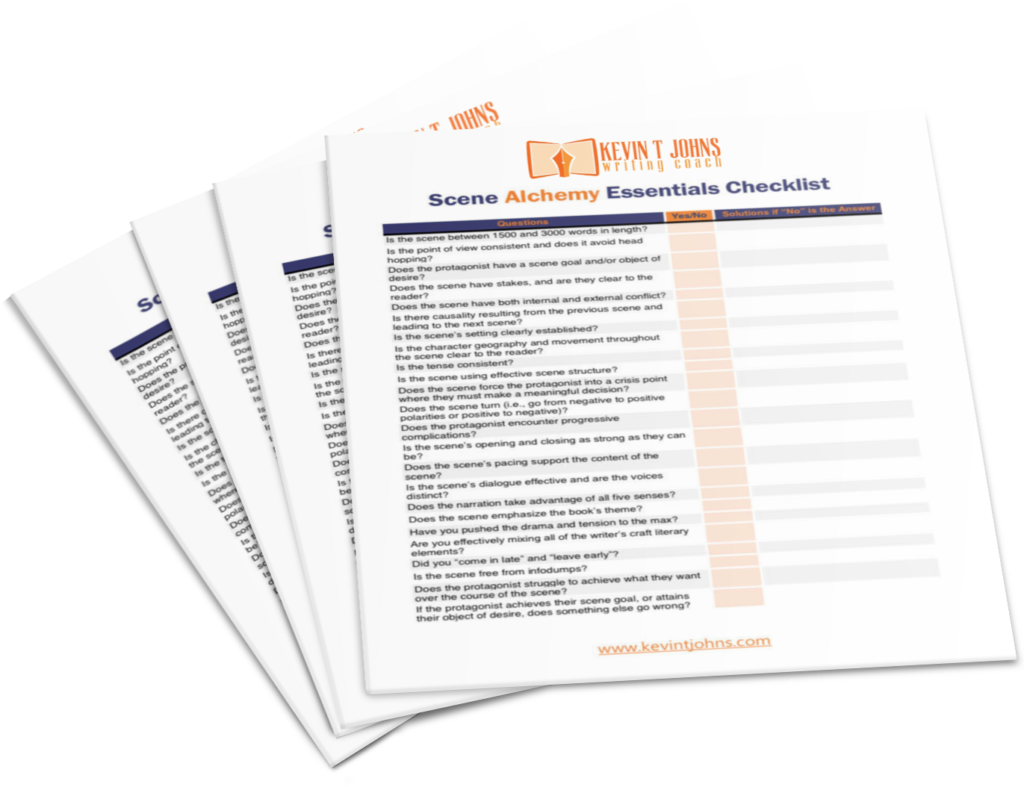

I this episode, we are continuing our exploration of my new tool, “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist.”

This checklist allows you to go over any scene you’ve written and ask yourself over 20 questions about it, so that you can transform an average scene into a piece of literary gold.

This is our third episode now going through the checklist. It’s got a lot of questions, and it’s got a lot of craft insight. That’s why we’re spending several episodes talking about it.

Let’s do a quick recap of the questions we’ve covered so far in the first two parts of this podcast series.

Is the scene between 1500 and 3000 words in length?

Is the point of view consistent, and does it avoid head hopping?

Does the protagonist have a scene goal and/or object of desire?

Does the scene have stakes, and are they clear to the reader?

Does the scene have both internal and external conflict?

Is there causality resulting from the previous scene and leading to the next scene?

Is the scene’s setting clearly established?

Is the character geography and movement throughout the scene clear to the reader?

Is the tense consistent?

Is the scene using effective scene structure?

Does the scene force the protagonist into a crisis point where they must make a meaningful decision?

Does the scene turn (i.e., go from negative to positive polarities or positive to negative)?

Does the protagonist encounter progressive complications?

Is the scene’s opening and closing as strong as they can be?

Does the scene’s pacing support the content of the scene?

Okay, so that brings us to:

Is the scene’s dialogue effective and are the voices distinct?

Now dialogue is obviously a complex and also very fun aspect of fiction writing, I have an entire course inside my FIRST DRAFT group coaching program on dialogue so I’m not going to dive into too much of it here other than to say that dialogue should move your story forward. It shouldn’t be expository. It should reveal character. It should have a sense of musicality or rhythm to it. It should use interesting or unique language. And it should have both surface text and subtext.

Now there’s a lot of things that you can watch out for in your dialogue writing, I often recommend trying to avoid long monologues or speeches by breaking up any piece of dialogue that has more than five sentences in it. How you can do that is you can use dialogue tags, you can use a piece of narration, you could use a piece of physical action or environmental description—any of these elements we can get in here to break up the dialogue.

The simplest approach, actually, to breaking up dialogue, and also ensuring that other characters in the scene have an opportunity to speak, is to simply have them say what the other character just said. If someone says, “The world is going to blow up! We need to get it out of here right now!” You can have the other character say, “Right now? This minute?” They’re not actually contributing a lot more to the scene, but what you are doing is 1) emphasizing an important plot point, 2) keeping that other character in the exchange and making it feel like a back-and-forth, and 3) it’s a chance to break up what could perhaps be a longer chunk of dialogue that starts to have that speech feeling or that monologue feeling. We’re not writing Hamlet folks. We are writing modern, contemporary fiction, and so we probably want to avoid those long speeches.

Another topic that maybe I’ll touch on quickly are those LY suffix adverbs. It’s a controversial subject. I think, ultimately, you just have to find for yourself what your level of comfort is when it comes to using adverbs. Stephen King says “The road to hell is paved with adverbs.” Whereas JK Rowling uses LY suffix adverbs in her dialogue tags constantly and is one of the most successful authors in the world. How you approach LY adverbs in your dialogue tags is up to you.

All right, so make sure that the dialogue in your scenes is top-notch.

Does the narration take advantage of all five senses?

As people and as writers, we tend to default to sight. If I asked you right now to write a scene about a library, you would probably describe the stacks, the books, the checkout counter, maybe you might describe the quiet sound, but there are so many other opportunities for description. There’s touch; how do the books feel? What does the carpet feel like underfoot when you step inside? What does the library smell like? Is it the smell of old books? Or is it the smell of a newly freshly painted wall? We experience life through a variety of senses.

In your drafting, especially in your first draft, you’re probably just going to default to what things look like. When you come back now—when you’re looking to take an average scene and make it extraordinary—that’s a great opportunity to ask yourself, “Is there a smell I could describe in this scene? Is there a taste I could describe? Is there the sound of birds chirping or of a fire alarm going off?”

We’ve got to get all these other sense descriptions into our story to really bring it alive. As well as to just provide a variety of descriptions and not always just be telling the reader the wall was white, the cup was red, that sort of thing.

Does the scene emphasize the book’s overall themes?

Now when it comes to themes, we can get pretty complex, but on the most basic level, generally, we have four or five topics that a book is dealing with that are the themes that are going to come back again and again throughout the story. We also have our controlling idea, which is the message of our story, and it’s usually the lesson that our protagonist learns or it’s the little piece of wisdom, that you as an author, are embedding into your narrative to share with the reader to give a little wisdom about what it’s like to be human and what it’s like to live life.

Every scene you write is ideally going to contribute to either the controlling idea, one of those half-dozen themes that you’re dealing with throughout the story, or both of those things.

Theme can be really useful when you don’t know what the characters should be talking about, or you don’t know how to describe a certain moment; return to your theme. If you’re writing a comedy or a romance, perhaps one of the themes in your book is misunderstandings. Characters are often misunderstanding things or getting confused about things. If you have two characters, and you just need them to spend some time together, what should they talk about? Well, maybe they should talk about confusion, or maybe one character should say something and the other characters should be confused by it.

We can do this thematic patterning as well from a character perspective. Perhaps you have a character who’s a construction worker and so whenever he talks, or whenever he has ideas, his ideas are always about breaking things down and building them back up again. Or maybe you have a character who’s a dentist, and they’re always talking about how we need to polish things up. We can use certain words or thematic concepts or ways of coming at things to distinguish character voices, as well as continue to provide thematic elements to our book.

What theme does is provide cohesion to our narrative. I see so many times in the manuscripts of first-time authors or in just the first draft of manuscripts where the book covers so many topics. There are so many things that it feels a bit unruly, and it feels like a bit of a mess to the reader. The more you can narrow down what the book is really about thematically, and the more you can hit on those thematic elements again and again, the more it gives a sense of unity to the narrative, the more it makes it feel like the book is about something that it’s not just all over the place.

This thematic unity also helps distinguish books within a series or distinguish your book from other books in your genre. There 1000 vampire books out there, but are there 1000 vampire books with a theme that’s education makes us better people? Probably not. But maybe that’s what your vampire book is about, so you’re coming back to this idea of what is a good person? What is education? How can it help us make us better people in the context of a vampire book?

Maybe you’re writing a romance series and maybe book five of your romance series is set on a ski hill. We have this theme of descent or this theme of ascent, or a theme of cold, crisp air, or of the colour white or of things freezing and melting. We can use all these thematic elements so that the reader is like, “Oh, yeah, Book Six. That’s the ski book. That’s the snow book. That’s different from Book Two, where they the character went on a vacation and fell in love in Jamaica, and everything was hot, and relaxing and fun.”

Again, identify the themes of your book, make sure you know what they are, or as they emerge in the drafting and revisions, getting more and more clear on what they are, then ask yourself anytime you’re looking at a scene, “How exactly does this scene contribute to the theme of the book? How does this support the lesson I’m trying to teach the reader or the character? How does this become an essential element to the larger hole that exists within?”

Now here’s a pretty fun one. Ask yourself, when you’re reviewing a scene:

Have you pushed the drama and the tension to the maximum?

I find so often as writers, we hold back. We don’t make things as interesting or as dramatic or as over the top as they can be. And obviously, there’s a fear of pushing into melodrama or pushing too far into melodrama and into that point of histrionics. But I can tell you personally, as a fan of literature, and as a fan of storytelling, as someone who reads a lot of rough manuscripts, writers are almost never going too far with their drama. They’re almost always holding back and not going big enough with it.

Which is fine. That’s what revisions are for. But when you are revising, get in there and push things to the max.

If you have a scene where one of the complications in the scene is your character stubbing their toe. Well, what if we push that, and they don’t stub their toe? Instead, they trip, and they break their leg. That’s a heck of a lot more dramatic. And it’s also going to have larger impacts on the narrative as a whole because the protagonist is probably going to be in a cast for the next six weeks or whatever in the book. Whereas if the character just bumps their toe, that’s not as dramatic, not as interesting, and probably has little ramifications on the rest of the book.

So really push things to the max and then see what it does for your narrative.

I have a bit of a theater background. I’ve been in half a dozen plays and studied theater in university. My wife went to a theater high school. So I have a little bit of experience with theater and something that we do in theater is called a “grotesque rehearsal.” This is when we’re getting near performance day, and the dress rehearsals are locked down. We then do a grotesque, which is where we push our performance over the top to the point that it’s silly and grotesque.

We go so far with our performance, and what we actually discover through the grotesque is how much we’re holding back, how far we can actually push our performance as actors before it does become a caricature, before it does become too melodramatic, or histrionic.

There is a wide girth of performance and of drama and conflict that you can bring to your storytelling or to your performance as an actor that you really don’t discover until you do push it too far.

So rather than playing it safe, rather than having things feel realistic, try pushing things to their absolute maximum and see what happens. I think it’s always easier to inch your way back from going too far than it is to have this book that’s kind of emotionally or intellectually safe and just doesn’t push the limits anywhere.

Take a look at your scene and say, “Am I really going to the max with everything that’s going on in this scene?”

I’m going to skip a question now because it’s a more complicated one, so we will return to it in the next episode. For now, I want to move on to a really simple piece of advice I heard at a comic book convention probably 25 years ago. I was attending a talk by one of my favourite writers and what he said is, when you’re writing a scene:

Come in late and leave early.

This advice can be SO useful.

Often, I see writers creating scenes that are so slow to get started, or we have these big recap paragraphs at the beginning. We’ll be halfway through the first page, and I’ll put a little note that says “This is where the scene actually begins.”

Come in late. We don’t need to see the boring part. We don’t need to see the person walking up to the other person to start the conversation. We can start with the conversation already underway. We also don’t have to linger with a character throughout the day until they go to bed at night. We can end the scene at the most dramatic point so that we create those cliffhangers and those open loops. We can leave the scene at the point of maximum conflict and interest.

Too often, writers stick around a little too long in the scene. You’re trying to wrap things up, but when we wrap things up, it gives the reader an excuse to close the book and go to bed. So come in late with the scene already underway, in medias res, and leave early leave at a dramatic moment that makes the reader think, “I absolutely have to turn the page and keep reading the next scene or the next chapter in this book.”

FIRST DRAFT

Now this is part three of our “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist” series, and if you’re enjoying this series, I really think you would love my FIRST DRAFT group coaching program.

We are bringing in a new cohort of writers for the first week of October and I’d love for you to be a part of it.

Inside this coaching program we have weekly question and answer live calls. We have weekly hotseat sessions. We have so much more, but what I want to focus on right now is that we have 20 writers craft online courses that address every single one of these issues that we’ve been talking about in this series. I’m just touching on them briefly here, but if you want to get into point of view, if you want to get into scene structure, if you want an hour-long course on dialogue, if you want to learn the mechanics of writer’s craft while also making major progress on your writing, and being part of a community of creatives who have access to a writing coach with over ten years of experience. I’ve worked with writers for decades. I’ve worked with thousands of them. I can help you write your book in a more effective manner and have more fun doing it.

I would love for you to be part of this cohort of the FIRST DRAFT group coaching program, so click here. There’s a sales page there with all the information you need about the program.

We have a monthly option where you can take things a month at a time, or if you want to take the leap and make the big commitment, we have a six-month membership where you can get in at reduced pricing. You get great savings with that six-month membership, so go check it out now.

Thank you for listening to this episode. This was Part Three of our Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist series. We’ll be wrapping things up in the next episode, where we’ll go over all the last questions in the checklist.

Remember to hit that subscribe button on your podcatcher of choice so that you don’t miss that next episode and so that I can see you there on . . . The Writing Coach.