In this episode of The Writing Coach podcast, writing coach Kevin T. Johns continues his review of the Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist tool and discusses:

- Using the four internal and four external literary elements

- Avoiding infodumps

- Ensuring your protagonist struggles to achieve their goals

- And why, even when your character achieves their scene goal, something else should go wrong

Listen to the episode or read the transcript below:

The Writing Coach Episode #174 Show Notes

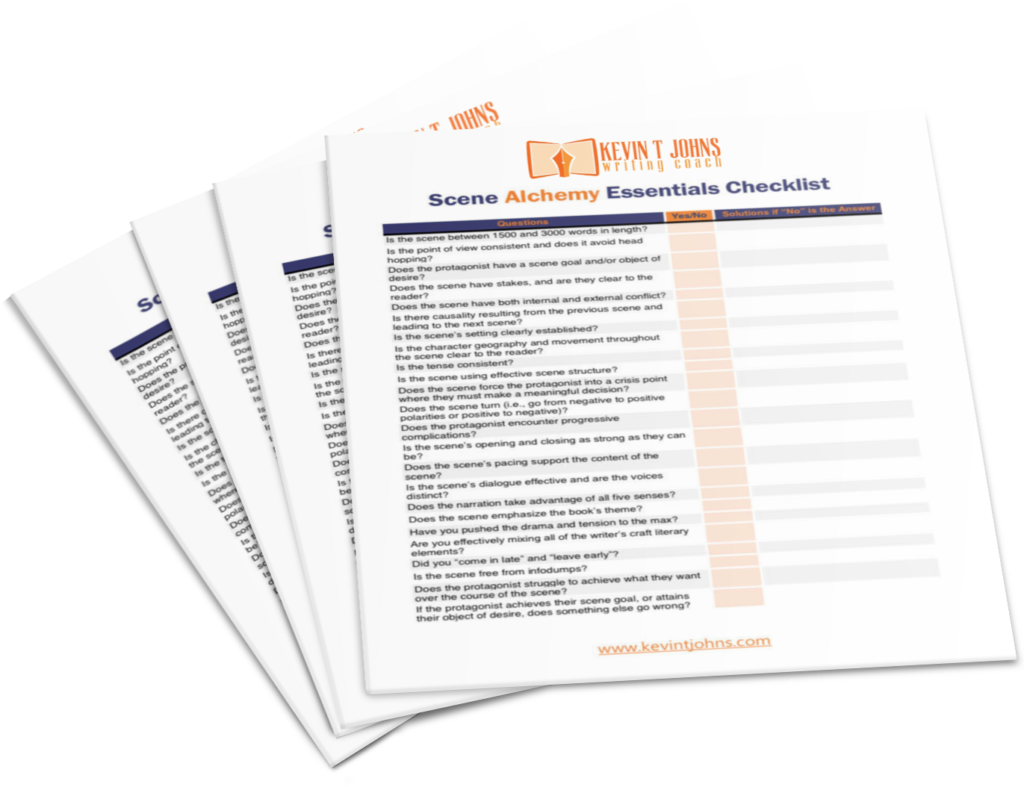

Download the FREE Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist Now!

The Writing Coach Episode #174 Transcript

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Hello, beloved listeners and welcome back to The Writing Coach podcast. It is your host, as always, writing coach Kevin T. Johns here.

This is part four, the final part in a podcast series, where we have been going over the questions in my new tool, “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist.”

Te goal of this checklist is to allow you to analyze the scene that you’ve already written and take something from okay or average and polish it up into literary gold. If you missed the first three parts of this series, don’t forget to go back and check those out. We’ve got over 20 questions we are using to analyze our scenes, but in this episode, we are going to go over the final questions in the checklist.

With that said, it is that time again: it’s that time of the year when I am opening the doors to my FIRST DRAFT group coaching program. We are welcoming in a new cohort. We want you in there by the first of October.

The first week of October, we’re kicking things off inside of FIRST DRAFT. We’ve got weekly question and answer sessions with me live. We’ve got weekly Hot Seat sessions. We’ve got positivity partner exchanges, over twenty writers craft training courses, and for each of them, we’ve got sketch notes, transcripts, and so much more.

FIRST DRAFT is a treasure trove of Writer’s Craft training materials, But it’s also an opportunity to get personalized coaching from me, as well as join a community of creative artists dedicated to writing.

Join the latest cohort of FIRST DRAFT now!

Now let’s continue our exploration of the Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist.

Last episode, I skipped one because it was a bit of a more complicated one and we were nearing the end of the episode. Let’s tackle it ow. The question is:

Are effectively mixing all the writers craft literary elements?

I like to see each of these literary elements included in every scene that you write for the most part. Now the thing is, there’s eight literary elements. That’s what I was saying it’s a bit more of a complicated one. But after saying that, I realized I already did an episode on the elements. So if you skip back about 10 episodes to Episode 164 of the Writing Coach podcast, you will see me go over those eight literary elements in detail.

That said, let’s go over them briefly again.

Now, to remind you of what we are talking about, I break the literary elements up into four external elements and four internal elements. The four external elements are environmental description. This is information about where the scene is taking place, the setting of the scene. Next up are physical actions and blocking, This is where people are located in that environmental space in relation to each other and to other objects, as well as what they do with their bodies over the course of a scene. Next external element is dialogue. This one’s pretty obvious. It’s what the characters say. The final external literary element is point of view character sense descriptions. We touched on senses earlier on another one of the questions, but sense descriptions are what the scene’s point of view character sees, hears, smells, tastes, and touches over the course of a scene. That’s a reminder that we don’t want to just default to sight even though that’s our natural instinct. That’s our four external literary elements are.

The four internal literary elements are internal thoughts and feelings. This is the internal experience of novels, the insight into our point of view characters’ minds, their souls. This is what differentiates fiction novels from every other art form. Next internal literary element is narrative exposition. This is the contextual information a reader needs in order to understand the story. Next up, big voice narration. This is when as a narrator or as a writer, you step back from say that close POV and you share some more general morals or observations or wisdom with the reader about life. Finally, our last internal literary element is recipes, rules, instructions, lists and rituals. This is specific instructional information contained within the context of the story that you’re telling.

We just covered eight literary elements, let’s go over them again, real quick. Environmental description, physical actions in blocking, dialogue, point of view, character, sense descriptions, internal thoughts and feelings, narrative exposition, big voice narration, and rules, recipes, instructions, lists and rituals.

What I see is writers tend to hit big on one, two, or three of these literary elements and forget the others. We might get a ton of internal narration and emotions, but we have no idea where the scenes taking place. Or we have a great dialogue scene, but people aren’t moving, and we don’t know how they’re interacting with their physical environment. When you’re analyzing your scene, take a look and say, am I mixing in all of these different literary elements into my scene?

Something I’d like to see you do is take that even further make sure you’re mixing them in together as though you were shuffling cards in the deck. I don’t want an entire page of narration, and then an entire page of sense descriptions; mix these things together over the course of your scene.

All right, next up:

Is the scene free from info dumps?

This is largely applicable to the first act of your book, and especially the first couple of scenes. I see it time and time and time again. As writers, we’re so scared to just drop our readers into the story, we feel like we need to give them our character’s life history, we feel like we need to give all this backstory and exposition and world-building. And what it becomes is just a big giant, ugly pile of info dumping and exposition. And that is the last thing you want to do if you want to pull the reader into the story.

Take a look at your scenes and say how much of this is really just exposition, and how much of it is absolutely necessary? If it is absolutely necessary exposition, is there a more palatable way to get it into the scene, as opposed to just dumping it in one of these big thick paragraphs of exposition?

In his book, Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook, Donald Mass has a really great exercise concerning first-act info dumps, which I think is fantastic. I would highly encourage you to use this technique when analyzing the first act of your manuscript. What he says is: look for any examples of backstory or flashbacks in the first act of your book, and then remove them, take those flashbacks, that backstory and drop it into Act Three. If it works in the context of Act Three, great! Get it in there and make that revelation about the past important to the latter portion of the book. If it doesn’t really fit in that latter portion of the book, just delete it because you probably don’t actually need it at all.

So that’s what this question is about. Are you avoiding info dumps? Take a look at that first act in particular, but the book as a whole, and look for giant chunks of exposition that either aren’t necessary or that could be communicated in a better way.

Next question:

Does the protagonist struggle to achieve what they want over the course of the scene?

This question is a culmination of a number of issues that we’ve talked about over these last few episodes. Largely this idea of does the character have a scene goal? Does the character have an object of desire within that scene? And then, do they encounter progressive complications and obstacles that get in the way of them achieving that scene goal?

You’d be surprised how often I read draft scenes in manuscripts where the character doesn’t have a scene goal. They’re just kind of floating through the scene, learning things or talking about things or having things happen to them. Or, if they do have a scene goal, they achieve it. And they achieve it way too easily.

We don’t like it when characters are just handed their goals. We want to see them struggle and then learn to overcome those obstacles and goals. That’s what makes a hero. That’s the lesson learned from storytelling: yeah, life is going to be hard, but you can overcome that if you persevere and if you develop a community, if you develop skills, if you get the right tools. That’s the message that we’re telling people. And when we have characters who are just handed their goals without struggle, it zaps the storytelling of drama of conflict and energy.

It also feels completely divorced from real life because real life is so damn hard. We all struggle every day to do well at our jobs, or to learn new information, or to be a parent, or to be a community member, or whatever those things are in our lives . . . to make money, to put food on the table. None of that is easy. And so when characters easily achieve their scene goals, it doesn’t feel real to life, and it doesn’t feel meaningful.

Let me give you two examples of this. Rey is one of the characters in the Disney Star Wars sequel movies. In that series, right from the start, Ray is an incredible pilot. We have no explanation at all for why she’s a great pilot, she just is. She also has an immediate affinity with the force, she’s just instantly able to use the force and instantly able to use a lightsaber. She is seemingly a better mechanic than Han Solo, a better sword fighter than Luke Skywalker . . . every single skill that the characters in the original trilogy struggled to attain she is handed at the beginning of her story, and so it never really feels like she struggles or grows or even changes because there is no change arc to go on when you start the scene or the story as already having achieved all the goals someone could want. Rey walks through the Star Wars trilogy being cool, being awesome, and it all ends up feeling meaningless because she didn’t really struggle for any of it.

Same thing with a more recent example in Star Wars. Just last week, an episode of the series, Ahsoka came out, and for the first six episodes of this show, the MacGuffin, the story goal for the character Sabine has been to rescue this character, Ezra, who’s been missing in another galaxy. Now in this episode, Episode 6, Sabine makes it to this other galaxy. And then she’s captured by the bad guys, and the bad guy to say, “Oh, we’re gonna let you go look for Ezra because you’ll never find him. He’s probably dead and leaving here means you will surely be dead as well.” Sabine is like, “I don’t care. I’ve come this far. I’m going to go find him.”

She heads out into this terrible deadly terrain, and she gets attacked by some bad guys. She easily kills all five of them. That’s her one challenge along the way: five bad guys who she easily beats. She then runs into some aliens who lead her directly to Ezra. It doesn’t feel like she struggled at all, it doesn’t feel earned.

We’ve spent this whole series building up this idea that it’s going to be so difficult to get to Ezra. And then, within 20 minutes of an episode, Sabine fights some bad guys, some faceless bad guys, some forgettable stormtroopers-type people, and then she goes and finds what she was looking for.

It’s underwhelming and it’s not dramatic. And it doesn’t feel like life.

Like we talked about, life is hard. Achieving big goals is hard. And so we just hand things to characters, throw some simple challenges in their way — it’s not good enough. They need to struggle, they need to have a hard time achieving those scene goals.

So take a look at your scenes and say, “Is my character achieving what they want too easily? How can I make things more difficult? Can I add complications?” If there’s already complications, “Can I make them progressive? Can I make the stakes bigger?” If there are already escalating stakes and progressive complications, “How can I make the protagonist suffer more? How can I make them have to give up something in order to achieve this goal?”

All right, we are at the final question. We’ve spent four episodes going over this worksheet but the final question in the Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist. This is the question:

If your protagonist achieves their scene goal or attains their objective desire, does something else go wrong?

Now, this was another problem with this week’s episode of Ahsoka. At the end of the episode, Sabine finds Ezra, and they hug and it’s like “we finally found each other,” the end. Again, there’s nothing dramatic about that; great, they found each other.

And when you’re writing a book, at the end of every chapter, your reader is always looking for an excuse to close the book and go live their lives or go to bed. You’ve got to keep them on the edge of their seats, you’ve got to keep them wondering what’s going to happen next.

And one of the best ways to keep them turning those pages is to prevent your protagonist from achieving their scene goals. They keep struggling and then not getting the thing that thereafter. That said, once in a while, we do need characters to achieve their scene goals. If you’re writing a mystery, and your detective goes to a crime scene, looking for evidence, you need them to find some evidence to push the story forward to the next part of the investigation. But if all they do is find that evidence and go great, we’re lacking drama, we’re lacking conflict. What if they find a piece of information or a piece of evidence, but that evidence points to their own best friend? Right?

So this is what we’re talking about when we say if a character achieves their scene goal, does something else go wrong? Is there still drama? Is there still conflict in the story? Take a look at those scenes where your character, even if they do struggle, and then attain their scene goal, look for a way for something else to go wrong.

I think this is how Cathy Yardley breaks it down, she says, here’s the three ways to end a scene: 1) Your character doesn’t get what they want. 2) Your character doesn’t get what they want, and something else goes wrong. Or 3) The character does get what they want, and something else goes wrong. Did you notice anything there? Cathy Yardley is saying either they don’t get their goal, which is which is drama and conflict, or they don’t get their to their goal and something else goes wrong, which is an escalation of the conflict, or they get what they were after but something else goes wrong. We have got to get the conflict in there. Nowhere in there does she say “your character gets what they were after in that scene, the end happily ever after.” That guarantees a reader closes the book and says. “Well, maybe I’ll pick it up in a couple of days or whatnot.”

All right, so That is the Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist and you can get it right here.

This too is the result of me reading drafts of writer’s scenes for the last decade. These are the twenty or so things that I’m looking for every time I’m reviewing a client’s pages in order to help improve them, help turn them into literary gold.

And that is what we’re doing every single week inside of the FIRST DRAFT group coaching program and community.

Our doors are open right now. I’m releasing this Monday, September 25, 2023. By the end of this week, we need you inside of FIRST DRAFT.

It’s an incredible program that is going to help you overcome some of the biggest challenges that writers face when trying to complete the first draft of their book.

You probably know already the amazing content within this program—there are a ton of supports, a ton of community interactions, and an amazing bounty of training resources for you there—but what you might not know is just how much fun and focused productivity we have within this program.

Some people are worried this is going to be too intense for them. They’re worried they’re not going to have the time to contribute to the program or to achieve their writing goals. But this program is reasonably paced. This is not about all-nighters. This is not National Novel Writing Month.

As much fun as people have with National Novel Writing Month and as much as it’s helped writers get started writing a book or maybe complete the first draft of a book, it’s not a sustainable process. And while you learn a tlot, you don’t necessarily add to your Writer’s Craft toolkit. You gain the experience of knowing “Oh, this part was harder, this part was easier,” but you don’t gain the knowledge of how to fix the problems or how to prepare for the obstacles so that you’re able to overcome them when they come along the way.

That’s why most people FIRST DRAFT for a one-time payment of $1,400 For a six-month membership in the program. If you broke it out over monthly payments, it would be something like 233 bucks a month. Not hugely expensive. But what it does is it gets you the accountability, it gets you the community, gets you the coaching, and it gets you the support to stay on track month after month after month, so that you don’t have to put your life on hold, so that you don’t have to sacrifice time with the kids, or fall behind in the day job, or all the other responsibilities that you have in your life already on top of trying to get a book written.

Tis is not about pulling your hair out. This is not about stress. It’s about fun. It’s about education. And it’s about steady progress towards achieving your literary goals.

FIRST DRAFT is about achieving a well-written first draft of your book that reads like a third draft, that was actually fun to write and didn’t feel like banging your head against the wall for six months straight.

I want you to join FIRST DRAFT now.

We’re welcoming a new cohort of writers into the program this week.

We kick things off the first week of October. We start going through those twenty writers craft courses, we start learning, we start growing, we start setting goals and tracking progress. It’s an incredible program, lot of fun, and we want you there.

If you are nervous about it, if you’re unsure, if you’ve never joined a program like this before and you are not sure if it’s going to be a good fit for you: choose the month-to-month option.

You can join for $350 a month and check it out for one month. If the program isn’t for you, then you leave at the end of the month. There’s no commitment for long term engagement. You’re paying month to month and you can leave anytime.

But what I find is most people discover how much they love the program, and they make that upgrade to the six-month one-time payment at a later date. So if you’re unsure of whether you want to go for the six-month commitment or not right now, just go in for a month. Check it out for a month. I am so confident that you are going to absolutely love this program and that you are going to kill it with the writing of your manuscript.

I want you to get in there, so sign up now.

That is it for this episode. This brings our series of examinations of the Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist to an end. Thank you so much for listening. I hope you found these last four episodes helpful. Remember to hit that subscribe button, and I will see you on the next episode of The Writing Coach.