Inspired by a Simon Sinek quote about arrogance and humility, host Kevin T. Johns explores how the modern view of writing as a talent differs from its historical roots as a trade in this episode of The Writing Coach podcast.

He explores how ancient scribes and medieval monks approached writing as a form of labour and how during the Renaissance writers were integrated into guilds and apprenticeship programs.

This episode will show you how embracing humility and pursuing apprenticeships can help you better understand writing’s mechanics as both an art and trade.

Listen to the episode or read the transcript below:

The Writing Coach Episode #197 Show Notes

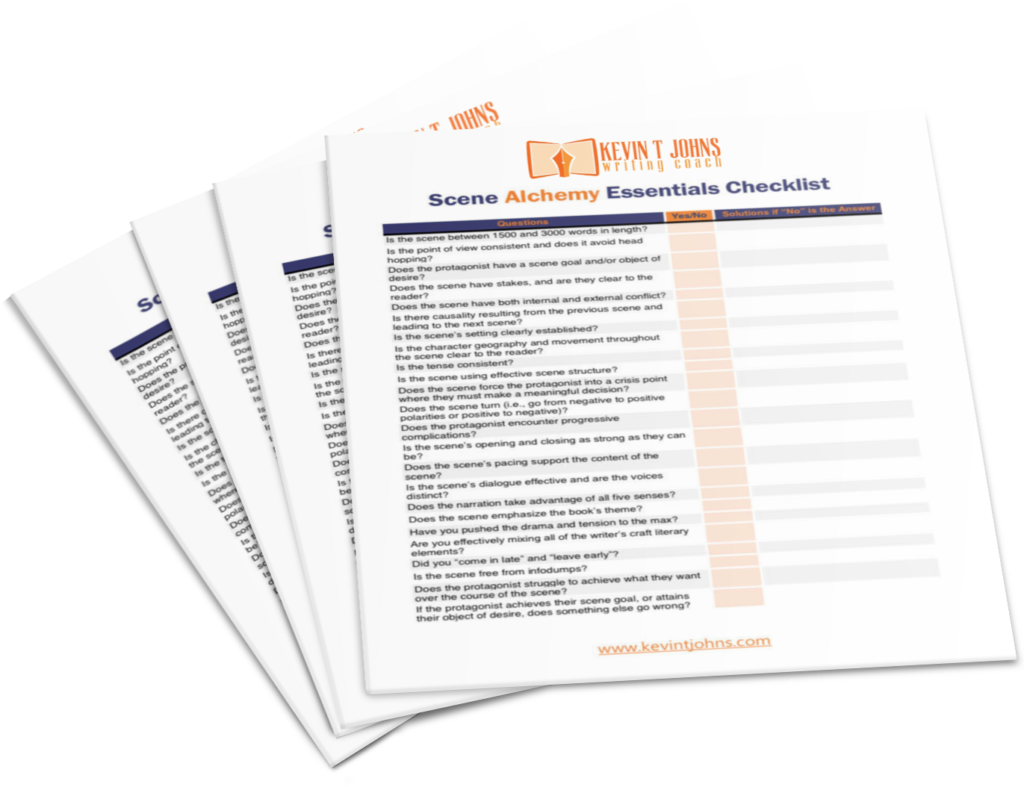

Download the FREE Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist Now!

The Writing Coach Episode #196 Transcript

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Hello beloved listeners, and welcome back to The Writing Coach podcast. It is your host, as always writing coach Kevin T. Johns here.

If you are looking for a simple tool to help you improve your scene-by-scene writing, head on over to www.kevintjohns.com/alchemy and pick up the scene alchemy essentials checklist. It is a checklist of questions you can ask yourself about any scene you’ve written so that you can turn an average or okay scene into literary gold.

Now, the Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist is rather apropos for me to promote at the beginning of this episode because it is a revision tool. Writing is iterative, and we need these sorts of tools to help us take a first draft and turn it into something better.

Now, I saw a post from Simon Sinek about this on LinkedIn this week. I am not a big social media guy. But for some reason, I’ve been getting a bit of a LinkedIn itch in the last couple of weeks, so I’ve been poking around and making some connections on LinkedIn a little more than I have in the past. But Simon Sinek is a speaker and an author. You might know him from his very famous talk; I think it might be the most famous or one of the most famous TED talks of all time: Start with Why. I highly recommend that you check it out. It’s applicable to writers even though Sinek is largely a business strategist, and he’s talking about what drives successful businesses in that talk.

What he says is that talk is that people don’t buy the product they buy, why you make the product. This is really applicable to writers as well; knowing your why, knowing the reason that you are embarking on any writing journey is super valuable on at least two levels.

One: it’s a touchstone; it’s the thing that you can go back to when writing is getting tough, when the writing is getting difficult, and when the energy or enthusiasm is starting to wane. And you’re starting to question yourself, and you say, “ Is this really worth it at all?” You go back to your why. And you say, “Yeah, it is worth it. This is the reason I started this project to begin with. And this thing matters.”

Two: going back to Sinek’s side of things where he’s talking to a certain extent about marketing and how you communicate what it is that you make. As a writer, your why is a wonderful thing to talk about. You don’t want to be interviewed on a podcast, TV show, radio, or what have you and just say, “In my book, this happens, and this happens. And then this happens.” No one really cares about that. What they care about is why you wrote this book to begin with and so that is why the talk Start with Why is hugely valuable for everyone, especially the writers listening to this episode of the podcast.

Sinek posted something on LinkedIn this week. It was just one of those quote images where you have some words in the square, but what he posted I thought was really, really interesting and applicable to my world and your world, which is the world of writing. Now, the post said was:

“Arrogance is thinking something is perfect after the first draft. Humility is knowing there is always room for improvement.”

You know, this touches on that Hemingway quote that I love so much and that you might have heard me share in the past, which is the statement:

“We’re all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master.”

That’s really what Sinek is saying here: experienced, knowledgeable writers know that there’s always room for improvement and that we can always come back and improve things on a later draft, whereas it’s arrogance to think that you got it all right the first try.

What I’ve seen in the writing world reflects this perspective that Sinek is sharing, and yet, I would argue it isn’t so much arrogance that drives this thinking, this idea that I’m going to get it all right on the first try. I don’t think most of the writers I work with or come into contact with are coming at this belief from a sense of arrogance. Rather, I would say that in the writing world, it’s ignorance. Ignorance is thinking something is perfect after the first draft.

To clarify, I’m not talking about ignorance in terms of bigotry or something; I mean ignorance in terms of a lack of knowledge and understanding of the nuance of the process.

And where does this come from?

Well, we all have grown up over the last 150 to 200 years, in a world where there is this myth of the natural-born artist, this individual who has been blessed by the Muse and imbued with this natural-born talent, they just sit down and they write their masterpieces, and perhaps the creative spirit flows through them.

This concept of the artist as this kind of special, talented individual is not that old. It really goes back to the 19th century and the Romantic poets in England. There were two generations of the Romantics. There were Wordsworth and Coleridge, their generation, who were really the forefathers of the Romantic movement, and then we had the New Romantics, which were Percy Shelley, Mary Shelley and Lord Byron. The point is that this group of writers in the 1800s publicized the idea of the poet as the individual who goes out in nature and is inspired by walks in the mountains and sitting by the lake and listening to the wind go through an Aeolian harp. (It’s been a while since I was at school, I might be getting Aeolian wrong.

This conception of the artist is largely an invention of a handful of writers, yet it has been the way that we’ve thought of writers and artists for almost 150 years now: the artist is a talented person who sees the world in a different way than the rest of us and is largely the product of luck and natural-born talent.

But guess what?

People have been writing for a heck of a lot longer than 150 years.

If this modern idea of the imbued artist is a construction of the Romantic poets that has stuck around for 200 years, what were writers considered before that?

Writers were tradespeople.

If we go back to something like ancient Egypt, there were scribes, and it was their job. They were highly skilled individuals trained in the art of writing. It wasn’t some sort of natural-born talent. It was a specialized skill that certain Egyptians took up as a trade, as a job that they got better at as they worked. These are the scribes that would maintain records. They would write letters, they would write legal documents, but they would also transcribe literature and religious tax, which is largely probably what we’re talking about on this show, right? (That said, I mean letter writers and legal document writers and in today’s world of email, being able to write any sort of communication is important.) But going back to ancient Egypt, there were people writing literature, writing religious stories down as a job, not as some sort of artistic endeavour.

If you continue forward in time, and we look at something like medieval Europe, this is where a lot of the people writing were monks and scholars. These were the folks creating those kinds of beautifully, meticulously handcrafted manuscripts from that medieval time. And they always have those amazing marginalia. And they’re always well, most of the time, they’re quite beautiful. (I studied medieval literature a bit in university and actually met my wife when we were both in a medieval play together, so I have a certain affinity for the scribes of medieval England.) That said, it was a means to preserve knowledge and pass down religious texts and histories.

But like I said, they were also beautiful. I’m not saying that just because it was a trade it means it was in a somehow purely mechanical process. Like I said, those books are beautiful. They are some of the most beautiful books you’ll ever see. They were skilled in their art but they’re ultimately a form of labour. It was a job that these monks and scholars were performing.

Things changed to a certain extent in that writing expanded out beyond the kind of elite, religious individuals and scholars during the Renaissance. We’ve got the advent of the printing press and suddenly, anyone can get access to written material, as opposed to just the ultra-elite having access to books.

But just because your average person could now write or hopefully read at least, it didn’t mean that the people creating that writing were now thought of as these special, unique artists. This was a time of guilds and professional associations, which were groups focused on the craft of the trade, writing and publishing. And like any tradesperson, writers of those times would go through an apprenticeship; they would work with a master and study under them.

I think this is one of the really big differences between writers for thousands of years and writers over the last 200 years. Most of the writers who sit down today to start their very first book have rarely worked in an apprentice-like relationship for any period of time or have worked under a master. Even those who have studied English literature, like myself, we really studied how to read literature, not necessarily how to construct it. And then I keep hearing from folks in MFA programs, where again, the mechanics of the novel are still never taught and focused on. Even in those programs, it’s more focused on how to capture your voice and how to write a beautiful sentence and how to just get words down on the page. But that trade-like approach of here’s the nuts and bolts of how to create a story is so rarely taught.

So people go into writing that first book really ignorant of what is involved. And so, as Simon Sinek points out, there’s always room for improvement. But again, unlike Sinek’s point where it’s a form of arrogance, I really think it’s just a lack of knowledge on the part of so many beginner writers. They sit down to practice a trade without judgment, training, and the knowledge to do it properly. I suppose there is a certain amount of arrogance involved in that, but you really can’t blame anyone when you don’t know what you don’t know and when the entire society presents artists as just these special, rare individuals. When writers sit down to write, they go, “Geez, I want to be one of those folks, I guess I better give it a shot,” but the reality is that if you don’t know the mechanics of your art form, you really don’t have much criteria upon which to judge the quality of your work. This is why writers will write a first draft and think that it’s good, even though it’s not.

Now, you might hear that and say, “Well, Kevin, whether something is good or not is just your judgment based on the preferences of the reader.”

I would argue against that.

Jennie Nash, who I had on this show many years ago and who’s one of the world’s top writing coaches, in one of her programs, I remember her saying, “Good writing is demonstrable.” It is not a matter of personal taste; there are facts involved that we can point to in order to determine whether a piece of writing is good or not.

Professional editors, agents, and writing coaches like me have criteria based on education in combination with practical experience that we can use to determine whether or not your writing is good. We also have advice and techniques that we can share to improve your writing.

I was just really jazzed up by this Simon Sinek quote, “Arrogance is thinking something is perfect after the first draft. Humility is knowing there is always room for improvement,” and whether it is arrogance, or whether it’s ignorance and lack of information that’s leading you to think you’re going to be able to write something perfect on the first draft, I encourage you to instead embrace the humility to know that writing is iterative, that there’s always room for improvement, that it’s going to take several drafts to get something right.

I would also encourage you to pursue that apprenticeship-approach. Take the courses, read the books, listen to podcasts, like this one, work with a writing coach like me so that you can have that period of apprenticeship and so that you can learn from a master and understand the mechanics not just of the art form that you enjoy, but the trade, the professional trade that you were taking on in becoming a writer.

We’ve been writing for thousands of years, and it’s only in the last century or so that we think it’s some special, unique, artistic, metaphysical act. Before that, for thousands of years, people learned how to write as a skill and they performed it as a trade.

So don’t lose the magic. Don’t lose the art. Create those beautiful manuscripts that those medieval scribes were able to create. But also understand that writing, like anything else, is a skill and a trade that can be learned, and you can do it.

If you’re interested in apprenticing under me, if you want to join one of my writing communities, head on over to www.kevintjohns.com You can learn all about my programs there. Or you can always shoot me an email at kevin (at) kevintjohns.com. Let me know what you’re working on. Let me know your thoughts on the podcast, and I will let you know whether I can help you get your writing to the next level.

All right, that is it for this episode. Thank you so much for tuning in. And I will see you on the next episode of The Writing Coach.