When I interviewed Shawn Coyne, author of The Story Grid, for one of the earliest episodes of The Writing Coach podcast, he stressed one of the most important skills a writer must master is how to craft a great scene.

I agree with Coyne.

In fact, one of the best pieces of writer’s craft advice I ever heard is related to a secret trick to improving scenes. The advice was given by acclaimed comic book writer Brian Michael Bendis at a comic book convention I attended over 15 years ago.

Bendis put it like this:

“The secret to writing a great scene is… come in late and leave early.”

What Bendis meant was that often we start our scenes before the dramatic thrust actually kicks-in, and then stick around too long, spending an excessive amount of time on the resolution to the scene’s conflict.

What this means is that we can improve the quality of our scenes by focusing on improving our scene openings and scene closings.

(Remember, a scene is one continuous piece of action within a linear timeframe and generally contained to a single location and point of view. A leap forward in narrative time, or a change in setting or point of view, usually marks the end a scene. For more info, check out The Difference between Scenes, Sequences, and Chapters.)

Upon reflection, you’ll be surprised by just how often one of your scenes can be significantly improved simply by cutting off the first few paragraphs or deleting the final few paragraphs. Through the act of trimming the shoe leather, you’ll focus the reader in on the most dramatic moments of your story.

This is what filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock was talking about when he said:

“Drama is life with the dull parts cut out of it.”

A trap many writers fall into when drafting the opening of a scene is to start with a description. I call this ‘It was a dark and stormy night’ Syndrome.

What time of the year a scene is taking place, or what the location of the scene looks like, isn’t nearly as dramatic a kick-off to a scene as a piece of dialogue (“Oh, my God! He’s dead!” cried Santa Clause) or a moment of action (Santa punched theEastern Bunny in the mouth.).

Hook the reader with something interesting and dynamic, then get to the scene’s inciting incident ASAP.

When it comes to closing a scene, you’ll certainly want to make sure you’re providing resolution to scene’s major conflict; however, you’ll also want to make sure you’re leaving “open loops.”

Open loops are unanswered questions that keep the reader turning pages and wanting to find out what happens next.

If you provide a perfect resolution with all the loose threads neatly tied-up at the end of a scene, your reader is going to say, “Great. This is a perfect opportunity for me to put down the book, turn off the lamp, and go to sleep.”

You don’t ever want to give your readers a reason to stop reading. Provide resolution to the scene, yes, but don’t stick around in the scene for so long that you bore the reader. Open a new door, or two, for every one that you close.

One of my favorite ways to end a scene with the “thrust and twist.” The thrust and twist is the idea that you want to end the scene by stabbing the reader in the gut… and then give the knife a twist. It’s like a cliff-hanger that shocks the readers on both an intellectual and emotional level. That’s the sort of thing that keeps readers turning pages.

Want to craft a great scene?

Revisit the scene’s opening and closes paragraphs and ensure your story-telling chops are firing on all cylinders.

—

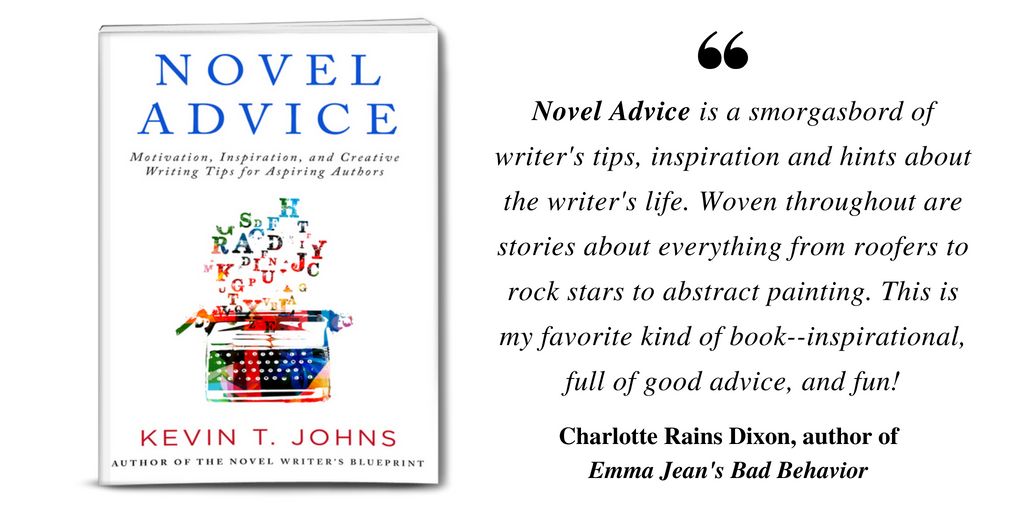

Enjoy this article? If so, you’ll love my book Novel Advice: Motivation, Inspiration, and Creative Writing Tips for Aspiring Authors. Grab a FREE copy by clicking the image below: